Sitting amongst my second grade classmates, I could feel excitement radiating throughout my entire body. Although the ancient gymnasium felt more like a sauna, no one was complaining. Suddenly, through the back door they came: men burst forth, all dressed in colorful red, white, and blue basketball uniforms…The Harlem Globetrotters! The next hour would be filled with awe-inspiring skill and entertainment, as our entire elementary school watched these amazing basketball players spin balls on their index fingers (and pencils- five at a time!), perform behind-the-back and between-the-legs dribbling, and sink what looked like 100-foot jumpers. Going home that day, I remember excitedly telling my dad, “I want to learn to spin a basketball on my finger!” “Well, son,” began my dad with a gentle smile on his face, “we should probably learn to dribble first.”

The fact is, just like athletes that show up to the first day of practice, writers bring different skill sets. Some arrive to middle school not knowing where to put a period, while others already know how to paint vivid pictures with words that knock our socks off. How do we plan for such a wide variety of writers?

Two weeks ago, I shared some thoughts on differentiation in the writing workshop, ideas learned from the fabulous Kate Roberts at a recent Teachers College Reading & Writing Project Saturday Reunion. In that post, I wrote about two main ideas that support differentiation in writing workshop: (1) keeping whole class instruction short, and (2) setting kids up for both a “main mission” and a “side mission” in their writing work.

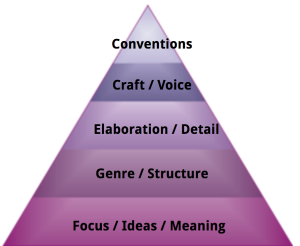

That day, Kate also shared some further ruminations that she hoped might help to create some traction when setting up the systems discussed in my previous post. Taking us back to a philosophical underpinning of workshop teaching, Kate reminded us that students become stronger writers- and things tend to go better – when they have the opportunity to practice. After all, we only get better at what we do! But how do writers know what to specifically practice? How can we help to make the path toward a goal more concrete and visible for our writers? We might consider an imaginary, or perhaps even a real, conversation with students that begins with the question, “What’s going to matter for you to work on for awhile?” To create a possible framework that might help to answer such a question, Kate proposed naming a skills focus/habit/mindset. When determining the direction a writer’s side mission might take, consider the following hierarchy of skills:

This pyramid is meant to represent a writer’s needs in order of importance, beginning at the bottom of the pyramid. I am conceptualizing it here in a way similar to Abraham Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs” (a psychological theory popularized during the mid-twentieth century with which I know many teachers are familiar):

- Focus / Ideas / Meaning : writers who struggle to create focus to ideas. If it’s difficult to understand what it is a writer is trying to say, this may be the place to start. Teachers may consider this to be perhaps the most critical tier of writing instruction; helping a writer to crystallize his ideas into a coherent group of thoughts organized around a central idea. If we read a student’s writing and can’t figure out what the writer is trying to say, Kate suggests that this is ground zero and we should probably intervene at this level immediately. This writer’s side mission probably ought to be around creating focus with ideas that help a reader to make meaning.

- Genre / Structure: writers who demonstrate needs in how to structure a certain kind of writing. If a writer already has a decent grasp of what her focus and (big) ideas are, then the next possible tier of writing skill might be working on how a particular type of writing is built. What kind of writing is this? A narrative? A review? An editorial? An explanatory piece? Teachers might negotiate a side mission with this/these writer(s) around structural practice.

- Elaboration / Detail: writers could use some help in effectively adding meaning. Should a writer already write with focus, getting ideas down in a fairly well-organized structure that matches a known genre or type, then perhaps a side mission in elaboration and detail may be in order. How do writers not only communicate and organize ideas, but effectively bring forth meaning? In narrative writing, perhaps it is selection of detail, or in argumentative writing it could be curating evidence. At this level of skill, writers need support in how they develop meaning through elaboration and detail.

- Craft / Voice: writers are ready for support in harnessing craft to add voice. These writers may have strong focus and ideas, know how to structure their writing, and are pretty decent at elaboration. They may be ready for us to teach into craft, showing them moves that writers make to enhance not only the meaning of the writing, but to strengthen their voice as a writer.

- Conventions: writers who demonstrate struggle with language conventions required in formal academic writing. Kate was clear that this level of instruction immediately bumps to “most urgent” if we are unable to understand a writer’s ideas due to weak language conventions. Advanced conventions usage may also be for more proficient writers, as well.

This list of skills organized in a possible order of importance allows teachers to negotiate side mission work with students. This is differentiation, as not every student is going to have the same side mission. It may be noted, also, that as you move up the pyramid, the work becomes more complex, allowing teachers a means by which to consider matching the appropriate “level” of writing work with each individual student.

But all of that said, how might a teacher go about launching such skills-focused teaching in a middle school classroom? Kate recommends beginning with the following:

- Collect and analyze student work.

- Confer with writers – talk to them and find out what their strengths and needs are!

- Assess on the run – research the classroom and make some notes.

After these steps have been taken, begin organizing small groups. At Two Writing Teachers, some wonderful posts have been written on small group work in writing workshop, such as Betsy’s recent summer blog series post on small group fundamentals, Melanie’s posts on her evolving chartbook, small group reminders, and ideas for planning small groups, as well as Beth’s instant minilesson follow-up post.

Kate’s final thought was to not avoid small groups just because we may not have the perfect plan! Without small group work, there really is no differentiation, for all students then get is whole class instruction and a little “waitressing” from us. They need more than that. “Doing a terrible small group is better than not pulling them at all,” Kate told us. For it is the act of attention and proximity that matters more than anything.

Just like I probably wasn’t ready to learn how to spin a ball on a pencil as a second grader until I learned more foundational basketball skills (like dribbling), some writers will need more foundational skills before they, say, begin tackling complex craft moves. Thinking about a sort of hierarchy of writing skills and then organizing students into small groups- even if they are not perfect! – may help you to meet every writer right where they currently are.

A huge thank you to Kate Roberts for the inspiration for this post. Look for her new book coming soon at Heinemann!

Just yesterday, I was conferring with writers about their first- of-the- year personal narratives. We all started with a simple graphic organizer. At the top was a space to state their topic and tell WHY this topic is important and define their purpose. Several students skipped filling in the “why” which, I now realize, speaks volumes. Others were less than clear about their purpose.

I experienced an AHA! moment in reading this post. Immediately, I recalled and identified the problem ice particular students has been exhibiting in her body of work. Lanny’s excellent chart surely will be an asset as I confer early on to be sure that writer has clarity of focus and purpose.

I have often repeated the mantra, “Identify the one thing you can teach this writer in this moment to move her writing forward.” Easier said than done, and I now realize I have

missed that mark all too frequently.

The path to identifying the greatest need in students written work has been amazingly clarified. I will face future conferring confidently using this excellent tool.

LikeLike

This is so helpful, Lanny! Thank you for sharing your thinking this way – will definitely bookmark this one!

LikeLike

Excellent blog! Very helpful.

LikeLike

Lanny, This post is going to be very helpful for my teachers who sometimes feel they’re not sure what a young writer should work on. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Awesome post

LikeLike