As we continue this blog series, I am reminded of the many turns I have made as an educator. The job can be fluid with frequent changes. We often have to adapt and shift to meet the needs of students before we know exactly what those needs are and sometimes before we have the right answers to grow our writers. No matter the writer’s age or ability–writing is hard. As I transitioned from nearly twenty years in elementary to middle school last year, I heard some of the same defeatist language emerge:

“I’m not good at writing.”

“I can’t do this.”

Not to be outdone by those silently waiting for the workshop to be over so they can leave and go to their next class while holding their breath, hoping I don’t walk over to check in on their progress.

Among many other challenges at the beginning of the school year, I knew building up writers’ identities would be a big hurdle. I also knew I might not get it right the first time. Much like I did not get it right in my earliest years as a preschool and kindergarten teacher. My understanding at the time was knowledge was something acquired, something I needed to deliver. I’m grateful to have a better understanding now, but I also find that old habits die hard when faced with new challenges like a grade level change. I heeded the words of Brian Cambourne in his book Made for Learning, where he reminded me in the early pages of his story about this misguided association I had with knowledge and its acquisition:

”Over the course of the past thirty years, what I’ve come to believe is that, as long as we (teachers and myself) continue to speak of knowledge as something “acquired,” we will continue to teach in ways that reflect a transmission model of learning, regardless of our voiced philosophical viewpoints. If we truly believe in constructivist models of learning and holistic models of teaching, we must also believe that learners construct their own meanings; they don’t “acquire” meanings, then our Discourse of Acquisition must also change.”

Crouch, Debra, and Brian Cambourne. Made for Learning: How the Conditions of Learning Guide Teaching Decisions. Richard C. Owen Publishers, Inc., 2020.

The bottom line, learning is and always has been the student’s job. One of my best tools to guide students in this construction is my feedback.

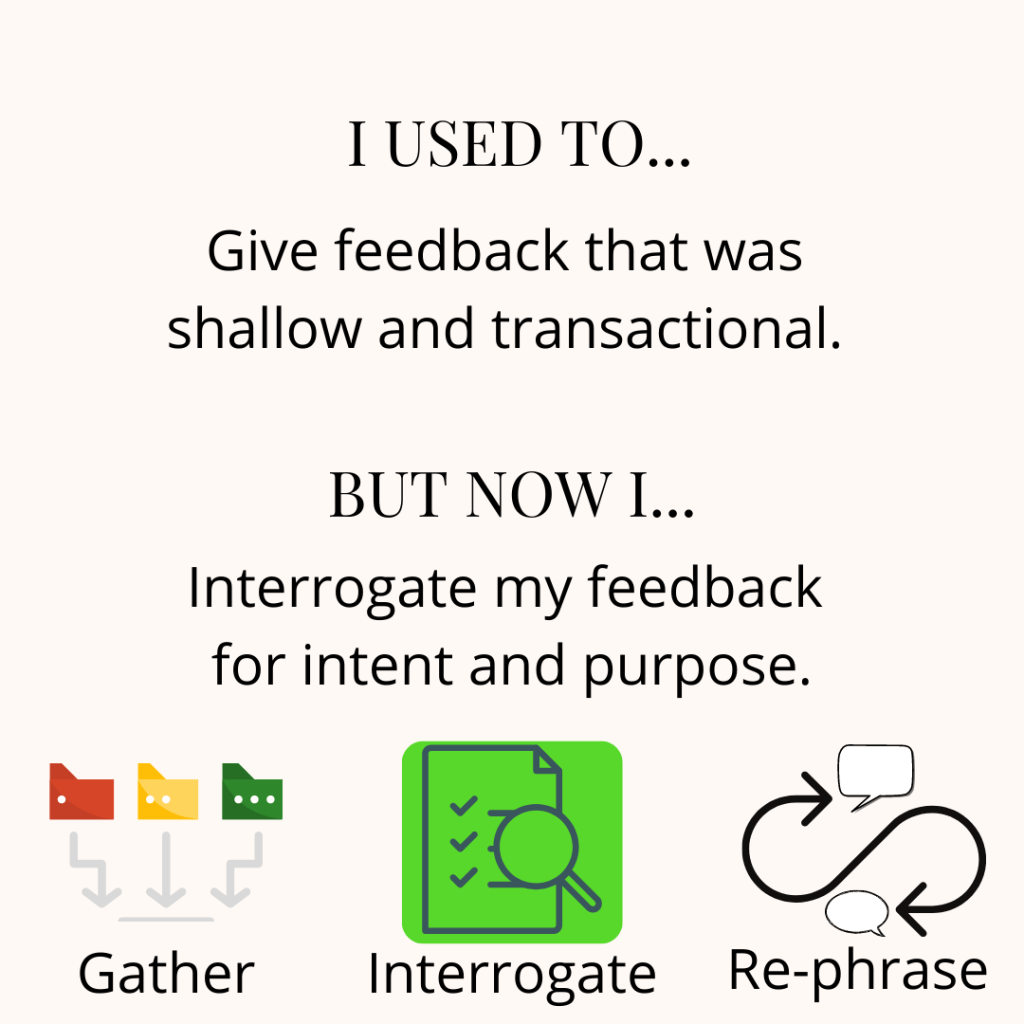

Reflecting on my early teaching days, I am reminded of the positivity I created and the community building that came naturally. However, I can’t help but reflect and think about the transactional ways I gave feedback. My words often giving an “if you do this–then this” kind of function. For instance, saying to a student, “Here is a note to remind you to use a capital I every time in your writing. When we finish the workshop today, reread to see if you capitalized I in your writing. This will make you a stronger writer.” The transaction being, I gave them a tool, so in my mind, this means I did my part, and the progress will now automatically occur.

This is a battle I continue to work through as a teacher of writers. Is my feedback transactional (if-then), or is it creating an environment for learning and meaning-making? Very often, the identities of my writers and how they see themselves in my classroom help me determine my feedback’s impact.

Here are three steps toward checking in on feedback and sustaining meaning-making environments in our workshop that build upon our writers’ knowledge when they walk in the door.

Gather

In your first weeks of school, gather your most frequently used feedback to students. What do you notice yourself saying frequently? You might begin to tally the frequency of feedback you are sharing. You may even start with a select group of students to make this gathering process more manageable. Pay attention and analyze what notes you are taking most frequently and determine patterns. Do you have a pattern of needs or a pattern in what you are looking for? Work to distinguish between the two since only one is about your writers.

When you determine some of these patterns, consider tallying to keep track of the frequency. This will help you with the next step.

Interrogate

After you have a collection of feedback, interrogate the words you are using. What are you saying, and is it conveying what you mean? Taking my earlier example–is my intent to have my students use a capitalized I, or is my intent to have my young writers use a capitalized I because they know it represents them, much like their name, which is also capitalized?

Other examples might include the commonly used “I like the way…” I think many of us have used this phrase as a way to keep our feedback positive. Although this is important, what we say after is equally important. Take a look at the difference in these two phrases:

“I like the way you are starting to use periods.”

“You are a writer who knows periods belong in your writing.”

Do you see the difference? We want to not only draw attention to positive approximation and progress but also capitalize on the writer’s engagement. From this example, you could direct the writer’s attention to a mentor text or modeled writing sample to determine where those periods go.

Re-Phrase

When my intent doesn’t match my words, I get a system in place. For me, this looks like a cheat sheet of phrases or stems to encourage my intent and deviate from what could be a habit or un-intended feedback that is shallow in its delivery.

As you begin to consider the school year ahead, I hope you find time to revisit your feedback practices. Gather, interrogate, and re-phrase when needed and of course, celebrate when your practices match your beliefs.

Giveaway Information:

This giveaway is for a copy of Answers to Your Biggest Questions About Teaching Elementary Writing. Many thanks to Corwin Literacy for donating a copy for one reader.

For a chance to win this copy of Answers to Your Biggest Questions About Teaching Elementary Writing, please leave a comment about this post by Thursday, 8/11 at 11:59 a.m. EDT. You must have a U.S. mailing address to enter the giveaway. Amy Ellerman will use a random number generator to pick the winners, whose names she will announce in an in case you missed it post about this blog series Friday, August 12th.

Please be sure to leave a valid e-mail address when you post your comment so Amy can contact you to obtain your mailing address if you win. NOTE: Your e-mail address will not be published online if you leave it in the e-mail field only.

If you are the winner of the book, Amy will email you with the subject line of TWO WRITING TEACHERS – AUGUST BLOG SERIES. Please respond to Amy’s e-mail with your mailing address within five days of receipt. Unfortunately, a new winner will be chosen if a response isn’t received within five days of the giveaway announcement.

Thank you for this post-I appreciate the list of examples for “re-phrasing” feedback! Such important reminders as we start the school year.

LikeLike

This post gives helpful examples of how to let the students do the work by giving clear feedback and asking questions.

LikeLike

Encouraging my intent with intentional feedback was a wakeup call for me. It’s so much easier to speak about the writing, when in fact, we are speaking to the young person and his/her ideas and expressions. In turn, it’s also part of trust building process. This was a critical reminder for me. I love the cheat sheet of phrases!

LikeLike

At a time when so many demands are being put on educators, this is a great reminder of how we can respond to students’ needs. Feedback can make all the difference and enable students to see themselves as writers.

LikeLike

I agree! To add on, it also makes a difference in that they see their ideas matter.

LikeLike

Such a great post, helping teachers think through the quality of feedback and whether it is simply transactional or is it creating an environment for meaning making. I appreciate the chart with suggested stems.

LikeLike