Estimated Reading Time: 5 minutes (870 words)

Audience: Teachers and Coaches, Grades K-8

A Backstory

About a year ago, I was sitting in on a Fundations lesson in a second-grade classroom. Midway through, the teacher addressed the class as “writers.” A little girl interrupted her and exclaimed, “You called us writers! This isn’t writing workshop. It’s Fundations!”

Smiling, the teacher gently explained that while it wasn’t “writing workshop” time, they were absolutely learning the skills writers use. In that moment, I was reminded how deeply students compartmentalize their day. To them, “writer” only exists in one block on the schedule.

Years earlier, when I was teaching on the Upper East Side, I had the gift of learning from the incredible Kathleen Tolan– staff developer, mentor, and friend. One day, we were watching my students work, theorizing about why they weren’t applying their word study learning to their writing, when she said:

“Well, Jess, have you ever told them that word study helps them read and write? Have you ever had them get their word study notebooks out during reading and writing?”

The answer was no.

It seemed so obvious. But I had never thought about it before. Of course the work should live side-by-side. Of course those notebooks should come out at the same time. I needed to make those connections visible.

Because while we know that the skills are intertwined, often our students don’t. To them, they are readers during reading workshop, writers during writing workshop, and word builders during word study time. But all of those identities support each other. They overlap. They depend on each other.

The question then becomes, how do we help students see those connections and support transfer?

Supporting Transfer Across Content Areas

Use the Same Language Across Subjects. Our students will transfer more learning if we use consistent vocabulary across content areas and make explicit connections.

Example:

“In reading workshop, you’ve been working hard to study words the author uses to describe the characters. As a writer, you can do the same thing! As you create your character, think about what words you want a reader to use to describe them.”

You might even invite students to pull out their reading notebooks and study how they’ve analyzed character traits– and then use those to develop their characters in writing.

Build Cross-Content Anchor Charts. Design anchor charts that intentionally mirror each other so students can see how their learning connects.

- A reading chart about using precise language to describe characters alongside a writing chart about using precise language to develop characters

- A phonics chart about syllable types next to a writing chart about spelling strategies to draw upon while drafting

- Even a math problem-solving chart that echo the reading work of identifying the main idea and using that determine what a question is really asking

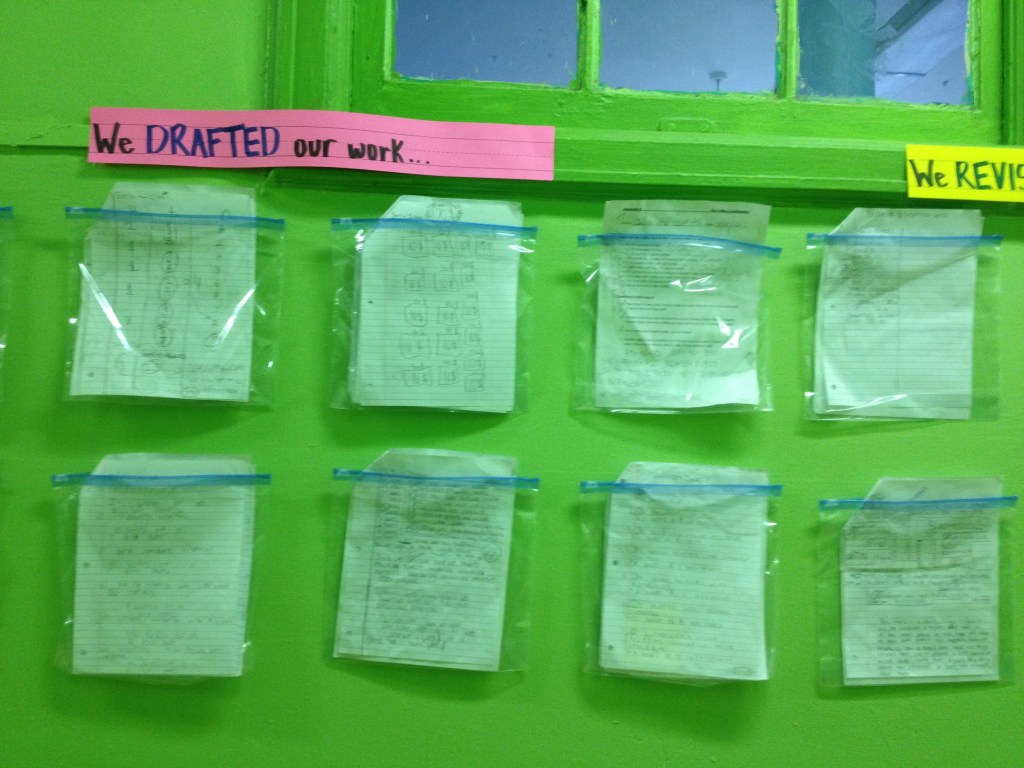

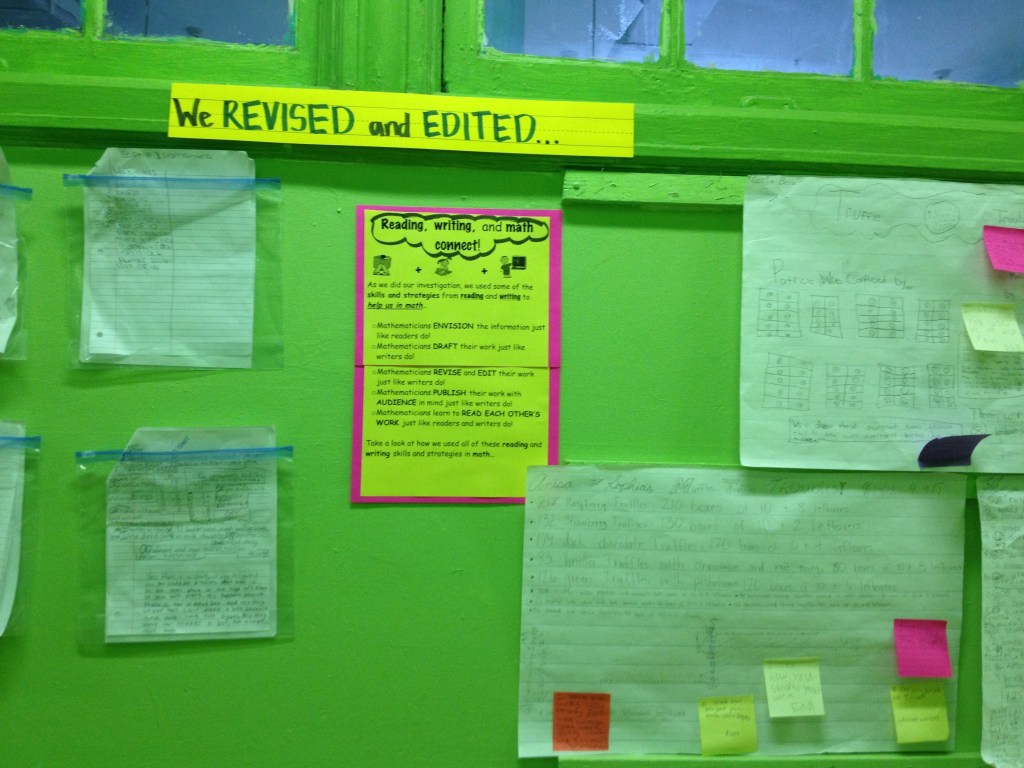

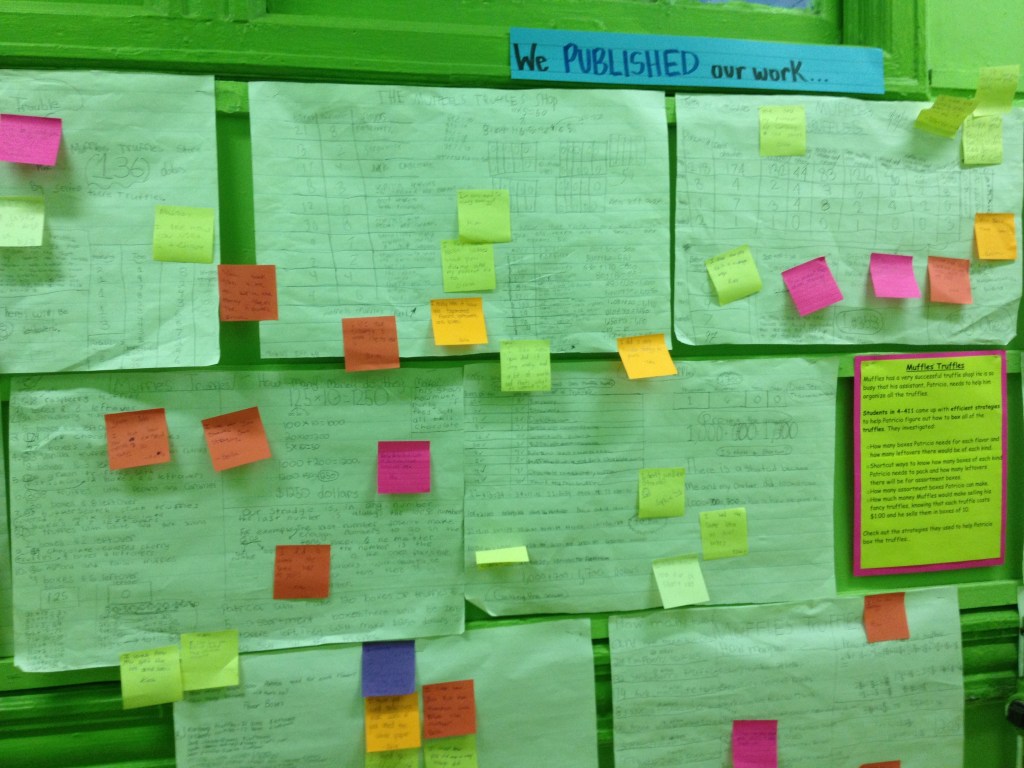

- Or a chart illustrating the stages of the writing process to support drafting, revising, and editing math, social studies, and science work

These visual parallels remind students that when they read, they are studying mentors–and when they write, they are imitating what those mentors do.

Use Notebooks Purposefully. Logistically, we tend to use separate notebooks for reading, writing, and word study. But there are things we can do to illustrate their connection.

A few options:

- Use one literacy notebook for everything to remind students that they are always “literacy learners.”

- Take reading notebooks out during writing time, to spark craft imitation

- Bring word study notebooks to writing workshop, to encourage spelling transfer

Helping student to see that literacy is big container, not separate blocks while help them implement their leaning across content areas.

Implement Cross-Content Book Clubs. Every so often, you might host a reading/writing craft club in your classroom. Encourage members to bring a book they’ve been reading and a piece of writing they’ve been working on. Have members identify a craft move in their books and help each other add that move into their writing. Celebrate the visible transfer work.

Use the Tally System. Ask students to make a tally each time they use learning from one subject in another. For example, students might tally when they:

- Use a word study strategy to decode during reading

- Draw on a syllable pattern to spell a tricky word in writing

- Apply revision strategies when working on a math poster

- Orally rehearse how an answer might go in science

The act of creating the tally builds awareness, and the tallies themselves become celebration-worthy data.

Model Cross-Content Transfer Yourself. Be cognizant of how often you try the above with your students. Make it a point to do this work yourself. Remember to:

- Walk over to a reading chart during writing workshop and name how you’re using it

- Grab a word study notebook to study a spelling pattern before drafting

- Refer to a revision checklist when editing a math explanation

Your modeling sends a powerful message to your students: literacy lives everywhere.

The Bottom Line

Transfer doesn’t happen automatically. It happens when we plan for it, name it, and celebrate it with our students.

When students begin to see reading, writing, word study, and even math as interconnected, they stop viewing their day as separate blocks and start seeing themselves as flexible, lifelong literacy learners.

Discover more from TWO WRITING TEACHERS

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I love the idea of having a mentor text/craft move book club! I’m envisioning a book bin that could be labeled ” lots of figurative language” or “Cool punctuation moves” ! How fun could that be? !!?!

LikeLike

love this!!

One notebook for everything might just be the connection

LikeLike

Love these immediately applicable ideas, thanks!

LikeLike