Estimated Reading Time: 6 minutes, 18 seconds (1262 words)

Primary Audience: Teachers or caregivers of young writers

The Context:

For young children, learning to communicate is central to navigating their world. From an infant’s earliest cries, laughs, and smiles to a toddler’s grunts, gestures, and attempts at spoken words, children constantly pursue meaning-making. Young children learn to communicate to meet their needs and make joyful and deep human connections. “Children read the world around them long before they read written texts. They use language to communicate with important people in their lives long before they read or write written texts” (Wright et al., 2022, p. 5).

Examining the evidence around what young children do when they write will lead us to better understand their conscious and unconscious purpose. We can also look at how teachers and caregivers nurture a social environment, giving purpose to children as they do this work.

Examine the Evidence:

Using Signs and Metaphors to Make Meaning:

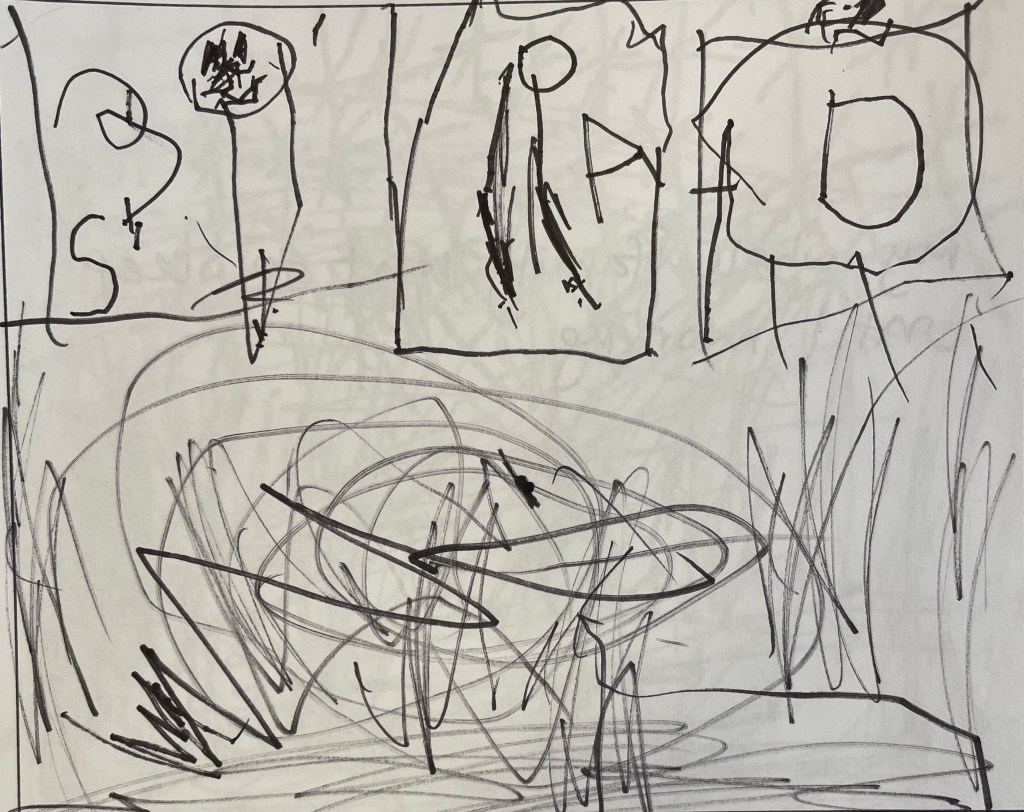

In Before Writing: Rethinking the Paths to Literacy, Gunther Kress describes a scenario in which a three-year-old boy sits on his father’s lap and draws a picture of a car. His drawing consists of seven circular yet undefined shapes. As he draws, he says, “‘I’ll make a car…got two wheels…and two wheels at the back…and two wheels here…that’s a funny wheel.’” Upon completing the drawing, he says, “‘This is a car’’’ (Kress, 2004, p. 10).

Toddlers and preschool age children operate within the realm of what Kress describes as “signs and metaphors.” According to Kress, “Signs arise out of our interest at a given moment when we represent those features of the object which we regard as defining of that object at that moment” (Kress, 2004, p. 11). For the three-year-old, “car-ness” is expressed in two ways: through drawing and through spoken words. The circles signify wheels, and the wheels represent a car.

As educators, we can glean so much information from what children do and say. The child’s purpose in drawing this car may not be known to him, but he is communicating a message or idea. He brings what he knows about a car from his internal schema into an external social world. Ultimately, at the very core of young children’s writing is something fundamental to the human condition as they are entering into the world of “meaning-making” (Kress, 2004, p. 12).

Gesturing to Express Ideas:

For infants and toddlers, using hand gestures such as pointing, clapping, and waving helps them communicate and meet their wants and needs. This instinct to gesture continues with young children as they go to school and become writers in a classroom. Gesturing can happen two ways: in the physical gestures that children and teachers use to point to and interact with parts of a picture and the literal gestures or marks made by a child on the page.

Dr. Deborah Wells Rowe, a preeminent scholar and researcher on early childhood writing, discusses the significance of gestures in an episode of Voice of Literacy (a podcast from 2019). She explains that a common gestural occurrence made by a child on the page is that of a circular or repeated motion. After talking with the child, they may explain that they are trying to convey a message, action, feeling, or event (Goodwin, 2019) with their mark-making. It may appear random or like scribbling to an outsider. However, representationally, the gestural mark expresses a great deal that they cannot yet convey.

Further, as the teacher interacts with the child about their work, they too may gesture by way of pointing to and touching the paper. The child may initiate or respond with their own gestures directed at the image(s) they made, and the teacher can engage the child in a conversation about it. Dr. Rowe states, “Gesture is something that’s produced for another person. It’s got an addressee. I want you to notice what I’m gesturing toward. So when children begin to gesture toward the page and they have a pen in their hand they often leave marks there, and then adults see those marks and start to talk about them. And that’s where this idea that the marks on the page are really significant starts” (Goodwin, 2019). As educators, we notice, wonder, and ask questions to help the child articulate the meaning behind their gestures as well as their underlying purpose: to express their thoughts and ideas.

Engaging in a Social World:

Children find purpose in writing when it is embedded within a social world. This aligns with how children learn best–in a language rich environment where they can communicate and interact with other children and adults. In her book Preschoolers as Authors: Literacy Learning in the Social World of the Classroom, Dr. Rowe studied the ways that two, three, and four year old children at an early childhood center in the Midwest found purpose in writing through the nature of their social interactions. Rowe asserts, “From the very beginning, the motivation for literacy learning is social…Conversations where children ask questions of others and talk about their own writing are much more than the setting for literacy learning. These exchanges play an important part in the process of writing and learning to write” (Rowe, 1994, p. 192).

In her study, Dr. Rowe found that during self-selected literacy activities at both the writing and art tables, children engaged with one another in the following ways:

- Interactive Authoring: When a child wrote something by themselves but spoke to other children as they worked and were sometimes influenced by their comments or by what others were writing.

- Interactive “Audiencing”: When a child came to a writing center and spoke to other children but did not write anything themselves.

- Individual or Parallel Authoring: When two children sat next to one another to write but generally worked alone.

- Negotiating Social Relationships During Authoring: When children wrote but spoke about things related to their social relationships and activities, not about their writing.

- Co-Authoring a Single Graphic Text: When two or more children worked together on a writing piece.

- Exchanging Literacy Products: When children gave written products to one another (i.e., cards, notes, or “mail”).

- Visiting the Center on “Business”: When a child came to a writing center to talk to someone but not to write. (Rowe, 1994, p. 61)

Children’s social interactions before, during, and after writing give them great purpose in doing this work. Sharing ideas, sitting side by side, asking and answering questions, talking about social activities, exchanging written products, and just being present at a writing center where others are working are highly motivating for children. They find great purpose in writing when teachers nurture classroom environments in which writing is part of the community’s social fabric.

Implications for Practice:

Before children learn to write conventionally, they operate in a world of signs and metaphors. A line or shape may represent an entire world if we are open to knowing and understanding it. When we respond directly to the information that children show and tell us about their work, we are better able to get to the heart of what they are trying to write and express. Early writing is gestural–both for the child and the teacher. One type of gesture is that of the handmade mark on paper. There is also the kind of gesture that happens through pointing to something for someone else to see or interact with. Both gestures are essential to the ways that young children find purpose in writing–by making their mark on the paper and sharing it with someone else with the potential for understanding. Young children find purpose in writing when given opportunities to engage with their teachers and peers, talk a lot, write together, and make things that others can touch, hold, and read. Writing is a shared experience and should be woven purposefully into the fabric of the early childhood classroom community.

Works Cited

Goodwin, A. (Host). (2019, October 7). Early Childhood Writing: The Role of Gesture with Dr. Debbie Rowe [Audio podcast episode]. In Voice of Literacy with Dr. Betsy Baker. https://sites.libsyn.com/469683/vol/early-childhood-writing-the-role-of-gesture-with-dr-debbie-rowe

Kress, G. (2004). Before Writing: Rethinking the Paths to Literacy. Routledge.

Rowe, D. W. (1994). Preschoolers as Authors: Literacy Learning in the Social World of the Classroom. Hampton Press.

Wright, T. S., Cabell, S. Q., Duke, N. K., & Souto-Manning, M. (2022). Literacy Learning for Infants, Toddlers, & Preschoolers: Key Practices for Educators. National Association for the Education of Young Children.

GIVEAWAY INFORMATION: This is a giveaway of How to Become a Better Writing Teacher by Carl Anderson and Matt Glover, donated by Heinemann. To enter the giveaway, readers must leave a comment on any BUILD YOUR EXPERTISE BLOG SERIES POST by Sun., 2/18 at 12:00 PM EST. The winner will be chosen randomly and announced on February 19. The winner must provide their mailing address within five days, or a new winner will be chosen. TWT readers from around the globe are welcome to enter this contest!

Discover more from TWO WRITING TEACHERS

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This article paints a picture of a joyful, purposeful writing classroom.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes – young writers seeing purpose in writing! This makes such a difference in their growth as writers. Thanks for this article. This is definitely one worth sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This blog offers may points for consideration.

LikeLiked by 1 person