Estimated Reading Time: 8 minutes (1,469 words)

Primary Audience: Teacher teams, coaches, and administrators

As scripted curriculum becomes more common in schools, teacher collaboration is even more essential. Programs offer structure and guidance, but it’s the collective expertise of teachers working together to problem-solve and respond to learners that brings any curriculum to life.

I meet with my grade-level team weekly. A running joke is that the meetings get heated. My colleague, Amy, and I are known to bicker like sisters as we dig into rubrics and standards. While it’s a funny joke, our passion and knowledge benefit our students. The team leaves the meeting with a shared understanding of student expectations.

Why It Matters

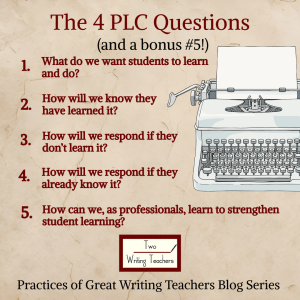

At our grade-level meetings, we follow the four questions of professional learning communities (Dufour, 2010) to guide our collaboration:

- What do we want students to learn and do?

- How will we know they have learned it?

- How will we respond if they don’t learn it?

- How will we respond if they already know it?

We also created our own Question #5: How can we, as professionals, learn to strengthen student learning? This question was answered beautifully yesterday in Jess’s post!

When teachers work together to unpack standards, examine student work, and create shared objectives, they’re practicing what John Hattie calls teacher clarity: a strategy shown to have a strong impact on student learning (Hattie, 2009).

Making It Happen

The thing about teacher collaboration is that it only happens when teachers have time (mindblowing fact, but it’s true!). Administrators can’t expect this work to occur magically unless they dedicate time, let teachers set the schedule, and then step back.

To support teacher collaboration, administrators may:

- Allot extra time for planning.

- Encourage teachers to set the agenda.

- Take something off teachers’ plates so they have the bandwidth to dedicate time to collaboration.

- Offer classroom coverage so teachers can observe how the same instruction plays out in another classroom.

- Empower teachers to make decisions based on the needs of their students, even if that means deviating from the resource.

Imagine If…

Each “imagine if” below demonstrates how my team gains teacher clarity through one of the four PLC questions.

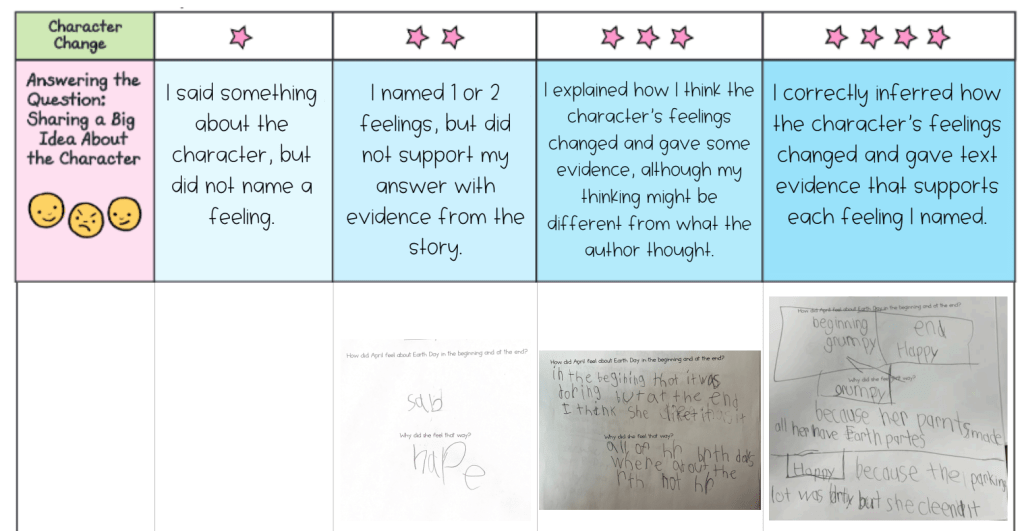

Imagine if teachers established shared objectives and learning progressions. (Question #1: What do we want students to learn and do?)

Some of the most effective goal progressions I’ve used with students weren’t copied and pasted from the lesson resource. They were created with my grade-level team while we reviewed student work. We even made copies of work from current students in the grade, which made the goal visible for students. As my teaching team grappled and argued over what the standard actually looked like, we gained more clarity, and students grew as a result.

Imagine if teachers wrote exemplar texts or demonstration texts together. (Question #1: What do we want students to learn and do?)

Based on this clarity, imagine if teachers wrote an exemplar text together. The text would match students’ interests and teachers’ expectations exactly, since it would be created by professionals who know the content and their learners. Options include:

- Start the meeting with 5-10 minutes for independent writing, then compare what the teachers created. Bonus: This gives teachers empathy for the student experience as they try to meet the curricular expectations themselves.

- Revise an exemplar text provided by your curricular resource so that it better aligns with your goal progression or students.

- Craft and revise a piece together, maybe even imagining what the piece would look like at each stage of the progression.

Teachers would leave the meeting with a piece they can use in a minilesson or as an exemplar. Teaching with this text feels more authentic because the teacher was part of crafting it.

Imagine if teachers scored student work collaboratively rather than individually. (Question #2: How will we know if they’ve learned it?)

Once a group of teachers is clear about what they expect students to learn, scoring becomes that much easier. Our team sits together and quickly sorts student work using the progression we created. When I’m unsure, my thinking partners are right there to help me decide where a student falls. Once we’ve all sorted, it’s much easier to look for trends with 100 samples in front of us instead of just one class. Use these groups to design minilessons or small groups to target areas of need and extend the learning for those who’ve mastered the goal. (To learn more about thin slicing, click here).

Imagine if teachers shared students, flexibly grouping kids into similar needs. (Question #3: How will we respond if they don’t learn it?, and Question #4: How will we respond if they already know it?)

Let’s return to the example above, where a whole grade of teachers has sorted students into three to five groups based on a learning progression. What if one teacher took each group for a targeted lesson? That would be more efficient than every teacher leading five separate groups.

My colleague Amy and I used a similar approach this year when reviewing phonics mastery checks. We realized that if we shared responsibility for the groups that needed reteaching, every student received more teacher face time and more targeted instruction. We each took on one phonics concept and planned one week of daily, ten-minute targeted small-group sessions. Each group included students from both classes who needed reteaching. The kids with the highest needs were in the groups daily, while a few others just attended two days. Since we each took a group, this freed up time to meet with the other students in our classroom, confident that everyone was getting what they needed, especially the kids who needed intensive review. As a bonus, sharing groups allowed us more time for enrichment, a group of students that often get overlooked. This works because Amy and I trust each other’s teaching, a result of the time we’ve spent together gaining clarity.

A note of caution: Make sure the groups are short-term and flexible to avoid “tracking.” Tracking occurs when students become “stuck” in a particular group without regular opportunities to move as their learning grows.

If this sounds overwhelming, try it just once for a week, as in the example above. As you practice and collaborate, it will likely become more manageable. This is a high-impact strategy that will lead to student growth if teachers have time to plan and problem-solve.

Imagine if teachers engaged in troubleshooting together. (Question #3: How will we respond if they don’t learn it?)

Whether the challenge is behavioral or academic, set aside time to vent and problem-solve together. When something in workshop isn’t working, it’s helpful to lean on the expertise of colleagues. Consider inviting a counselor, interventionist, gifted teacher, or special education teacher, depending on the context. Allocate time to problem-solve around instructional approaches, individual learners, and whole-group patterns.

Imagine if there were a space for teachers around the world to connect, share, and be inspired. (Question #5: How can we learn as professionals to strengthen student learning?)

A group of TWT readers has been meeting monthly to do just that! We start each meeting with a time to write, followed by a time to share what the breakout groups have been working on. Here’s what the breakout groups are up to:

- The mentor text group meets monthly. At each meeting, one person brings a mentor text and craft move list they’ve curated to share with the group.

- The book study group is reading and discussing 100% Engagement by Brian Sztabnik and Susan Barber.

- The teachers-as-writers group plans to begin meeting this month. Their goal is to set up a writing group for accountability. Melanie wrote more about this group on Sunday.

- The toolkit group will also start meeting this month to design and share writing toolkits.

Want to join us? Comment below and I’ll email you the details.

Giveaway Information

This is a giveaway of Daily Sparks: 180 Reflections for Teacher Resilience by Gail Boushey and Carol Moehrle, donated by Stenhouse Publishers (Routledge). Three copies will be given away to three separate winners. To enter the giveaway, readers must leave a comment on any Practices of Great Writing Teachers Blog Series post by Tuesday, Feb. 3 at 12:00 PM EST. The winners will be chosen randomly and announced on Thursday, Feb. 5. Each winner must provide their mailing address within 5 days; otherwise, a new winner will be selected. The publisher will ship worldwide so that anyone may enter.

References

DuFour, R., DuFour, R., Eaker, R., & Many, T. (2010). Learning by doing: A handbook for professional learning communities at work. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Discover more from TWO WRITING TEACHERS

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

What struck me was putting ourselves in our students’ shoes and writing, as part of identifying what we want our students to learn and do.

LikeLike