Estimated Reading Time: 6 minutes (1,205 words)

Primary Audience: K-12 Teachers and Coaches

Everyone who knows me knows I’m a runner. They see how I spend my time (early mornings on the run), how I spend my money (race entries and new shoes), and what I consume (running podcasts and books). They know because of the cliché “26.2” sticker on my car and marathon t-shirts I wear.

Everyone who knows an 8-year-old knows their identity is still developing. One week they dream of being a professional soccer player, and the next they’re set on Broadway stardom. As writing teachers, it’s our job to foster individual writing identity development. Writing identity is more than just seeing oneself as “good” or “bad” at writing. It’s an understanding of one’s unique voice, process, and purpose as a writer. Identity grows when students have a space to reflect, take risks, make choices, and recognize themselves in the work they create.

Why is identity important?

Many students struggle to see themselves as writers because they’re taught that writing is a rigid, step-by-step process rather than an individual journey. In Every Child a Writer, Kelly Boswell (2021) says, “One’s identity as a writer influences whether a person engages with writing or not.” If we want students to write, we have to help them see themselves as writers.

How does writing process relate to identity?

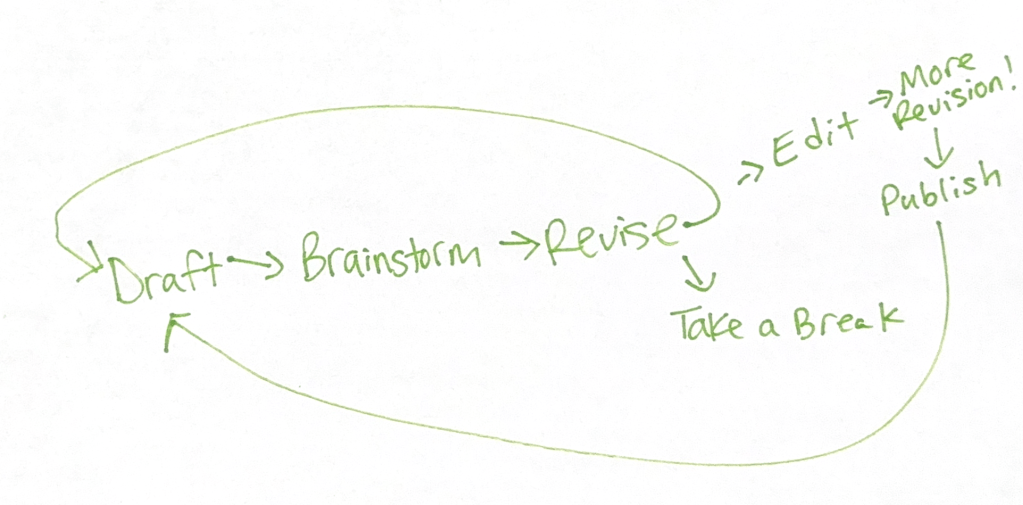

Reflecting on one’s thinking (or metacognition) is challenging for students. When students are able to articulate their unique approaches to writing, they begin to develop a stronger sense of themselves as writers. The writing process is not a standardized, linear, sequence, like this:

Rather, it’s a fluid, individualized process that writers develop themselves. For example, my writing process usually looks like this:

By encouraging students to cultivate their own writing processes, we support the growth of their writing identities. This approach is supported by research; The IES Practice guide recommends teachers “teach students to use the writing process for a variety of purposes. Explicitly teaching the different processes writers use and why helps kids develop as a writer and learn more about themselves” (Graham et. al, 2018).

After all, some of our students’ favorite authors DON’T follow a linear process to write:

Regardless of Your Script: Supporting student writing identity and an individualized writing process is the cornerstone of writing instruction. There are high-impact instructional shifts that bolster identity development, meet grade-level standards, and fit within any learning environment. As you’re unboxing a new year, grade-level, or curricular resource, consider grabbing a box of one of these fresh ideas to promote identity development in your writing classroom:

Grab & Go Box: Quick moves to build writerly identity now

- Make language shifts that center student ownership over writing. When conferring with writers, say things like:

- “I notice you’re the kind of writer who…”

- “You’re the author, so you decide.”

- “What are you planning to do next?”

- “What challenges did you face as a writer today?”

- “What did you learn as a writer today?”

- Read The Language to Develop Agency by Stacey Shubitz for more ideas.

- Utilize self-perception surveys throughout the school year to help students reflect and track how they grow and change. Check out these editable copies of writing surveys, and edit them to fit your needs.

- Teach students to define their writing process.

- Use the slides above to share how published writers navigate the writing process. Ask students to reflect on the author they identify with most. (Another fun resource is https://www.firstdrafttofinalbook.com/, where children’s book authors share pictures of their of well-known books as first drafts).

- Prompt students to reflect and map their writing process. Read Thinking About and Honoring Individual Writing Processes by Melanie Meehan to see student examples. Discuss the results and analyze what this says about us as writers.

- Allocate time. Many of the authors quoted above state the value of time. If your writing program doesn’t allocate a lot of time for writing (shocking, but it happens!) get creative about finding time for students to actually write. Write during morning meeting, for a brain-break after recess, or during dismissal.

- Be a writer yourself. Sit alongside your students and write. Share your work. Release the teacher-student power dynamic and converse with students as fellow writers in the process.

Home-Cooked Dinner Box: Deeper practices that take time (and are so worth it!)

- Plan opportunities for reflection to help students develop identity. One way to structure reflection is with reflective notebooks. Use a short, weekly routine and predictable questions, like I’ve outlined in Try Reflective Notebooks This Year.

- Offer more choice. In Joy Write, Ralph Flecther (2017) says, “Students really own the writing when they experience flexibility and freedom with topic choices” (p. 47). The Common Core State Standards outline the genres students should learn, but don’t state required topics. So why do so many programs and teachers mandate what students write about? Choice goes beyond topic, too. Empower students to choose their writing environment, tools, paper, and writing process.

- While trickier, explore opportunities for genre choice, too, like independent writing projects or Freewrite Fridays. Many critical writing standards can be taught outside the genre-box, and giving kids opportunities to explore other genres like fantasy pay dividends in identity development. (Bonus: Did you know fantasy writing fits within narrative writing standards? Challenge yourself to dig deep into the standards to widen the scope of what you offer students.)

- Balance high-stakes and low-stakes writing. One of NCTE’s (2018) core principles of writing instruction is that writers grow when they have a range of writing experiences. Additionally, the Common Core State Standards ask students in grades 3-5 to write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of discipline-specific tasks, purposes, and audiences. Ralph Fletcher (2017) argues that when students write informally, they’re more likely to use their own voice, which translates to higher-level thinking skills. Low-stakes writing can look like writing notebooks, daily warm-up prompts, or the Classroom SOLSC.

- Empower students to be teachers and experts. Peer-coaching helps students identify their strengths and grow their own skills. This might be as deep as planning student-led lessons or as easy as saying, “Jack is the one to talk to if you need help writing a graphic novel.”

So… why focus on identity?

Because writing identity helps students:

- Develop a process that works for them

- Build habits that support lifelong writing

- Decide to write- by choice, not just assignment

- Grow in both motivation and skill

Giveaway Information:

Want to win a copy of When Writing Workshop Isn’t Working (2nd Edition) by Mark Overmyer? Stenhouse Publishers (Routledge) has donated a copy for one lucky reader.

How to Enter:

- Comment on this post by Friday, 8/15/25, 11:59 p.m. EST.

Winner Selection:

- One winner will be chosen randomly and announced at the bottom of Sarah Valter’s post by Tuesday, 8/19.

Eligibility:

- You must have a U.S. mailing address to win this prize.

If You Win:

- You’ll get an email from Sarah with the subject “TWTBLOG – UNBOXING FRESH ROUTINES.”

- We’ll pick a new winner if you don’t reply with your mailing address within five days.

- Routledge will ship the book to you.

References

Boswell, S. S. (2021). Every kid a writer: Strategies that get every child writing. Scholastic.

Fletcher, R. (2017). Joy write: Cultivating high-impact, low-stakes writing. Heinemann.

National Council of Teachers of English. (2018, November 14). Understanding and teaching writing: Guiding principles. https://ncte.org/statement/teaching-writing/

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common Core State Standards for English language arts & literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Washington, DC: Authors.

https://www.corestandards.org

What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) Practice Guide: Teaching Elementary School Students to Be Effective Writers (Graham et al., 2018).

Discover more from TWO WRITING TEACHERS

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.