My colleagues laid our papers down on the table in front of us. No one spoke for an entire minute. I rubbed my chin, while others seemed to silently search for words. “Well,” I began, breaking the silence, “he’s definitely passionate about jaguars.” Others nodded enthusiastically, still gazing at the copies of the student’s writing in front of them. We were studying a seventh grader’s post argumentative writing on-demand, but it resembled more of … well, an informational piece…maybe? Although we definitely detected a great deal of background knowledge and passion for jaguars, it was not clear- at all- what this writer wanted to convey. Looking across at the child’s teacher, I said, “I think we need to start with some conferences around focus and meaning.”

At the heart of all great writing is meaning. Writers select details carefully and deliberately, depending on the message we wish to convey to readers. During a professional development workshop last year, author and speaker Kate Roberts suggested that writers who struggle with creating a clear focus (i.e., meaning) are sending us a signal that this probably needs to be our first conference or small group. For without a clear focus or organizing idea, writers can leave readers confused. And that’s not good.

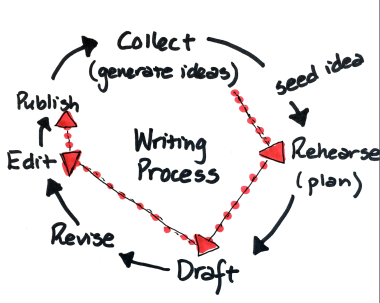

Thinking about meaning can probably fall anywhere in the writing process. But in writing workshop, perhaps one of the most important stages to teach into meaning is in revision. Oftentimes, this phase of the writing process does not receive the attention it really should, as student writers often either forget to make changes, or worse, resist this extremely important part of the process altogether. Young writers will often move through the process like this path (outlined in red):

Young writers often bypass revision, or only give it cursory attention.

One of the greatest gifts we can give our writers is teaching the value of revision. As all writers know, typically we do not produce our best writing in our first attempt. While those first drafts (or “fast drafts”) are important for getting some thinking and ideas down on a page, it is important that we teach them that through the revision process ideas become more clear, their voices stronger.

However, revision is not easy. And it is usually considerably ineffective to say to kids (as I did as a beginning teacher), “Okay, today is revision day. So, go revise your papers.” Most of us know this is likely not the path to creating stronger revisers or writers, so we typically teach revision strategies. Without strategies, I find student writers will mostly engage in what I call “tinkering,” a somewhat piecemeal practice in which they engage in changing a word (or two) here or there. This is not revision!

One way we can teaching into this is by teaching students to revise in service of meaning. According to teacher and Teachers College Reading and Writing Project Staff Developer Pablo Wolfe, the best revision comes when kids know what they are really trying to say. This is likely true. But how can we help our writers do this work?

Revising for Meaning

Long Writing to Identify Meaning – Pablo suggests that one possible way to help kids think more deeply about meaning in their writing begins with writing about their writing. Similar to thinking on the page that we sometimes invite readers to engage in, this strategy is meant to harness the power of thinking with pen in hand. A famous writer once said (I’m paraphrasing here), “I don’t know what I think until I write it down.” Students can lean on such prompts as:

- “Maybe what I’m trying to say is . . .”

- “Or maybe . . .”

- “Maybe I want my reader to think . . .”

- “Maybe I want my reader to feel . . .”

- I could have my reader feel/think ________ at first, and then I could have them feel/think ______ at the end.”

Like any strategy we want students to try out, teachers would need to model this, showing how writing long in this way can help us to think about: (a) what we are really trying to say, and (b) what needs to be changed, rewritten, added, or removed.

Although writing about your writing may feel strange or unnecessary at first, imagine the great gift such work might offer. Whether it be narrative, argumentative, informational, or literary analysis, this strategy holds the potential to provide a lens through which our writers can begin to see their piece in a new way– which is the point of revision.

Four Ways to Revise with Meaning in Mind

Depending on your writers, we can think about teaching the following ways to revise to a whole class, small groups, or in conferences. Or, perhaps your middle school writers might be able to latch onto one of these strategies with just a quick modeling and coaching session? Here are four ways to revise with meaning in mind:

- Write long about specific parts- Writers can draw boxes around specific places (e.g., beginnings, middle sections, endings) and write about what it is they are intending to show, using phrases like,

- “In this part I’m trying to say/show…”

- “In this part/scene, I want my reader to think/feel…”

- Revise dialogue/quotes to pop out meaning- In narrative writing, writers can think about what emotion or idea they are working to evoke in each section of dialogue they wrote. We can teach them to revise it by thinking about, “How can I make that emotion or idea even stronger?” Rewriting sections of argumentative or informational pieces that contain quotes might also be benefit from the same question.

- Change the ending so the meaning is natural, not just stated- Sometimes we encounter writers that want to hand us the ending, almost saying to us, “Here’s what I want you to think, okay?” Typically, professional writers like to leave some work for the reader to do. One way we can teach writers to honor readers a little more in this way is to model how we can craft an ending that allows readers to draw natural conclusions.

- Create a totally different draft that begins and ends in a different place- Revision can be a perfect stage for helping writers who struggle with volume. For writers who may need to just write more and can handle such a strategy (without withering before your eyes), we can coach them to strengthen their meaning by redrafting their writing piece, selecting a different beginning and a different ending place. I find many inexperienced writers provide unnecessary detail, especially at the beginning; this strategy can help them trim for more potent meaning.

By providing explicit teaching into revision, we do writers a great service. At my school, we hope to teach our student who loves jaguars some important lessons over the coming days. He has a great deal to say and demonstrates genuine engagement and enthusiasm for the topic. Which is great! It’s now just a matter of finding out what he really wants to teach the world; and that will take some revising for meaning.

I’m revising for meaning since I’m preparing a 400-page werewolf thriller for reprint. It’s been years since I’ve seen the manuscript and I know exactly what you mean about re-examining the motivational aspect of the story line. Thanks for giving me such great reminders.

LikeLike

Wonderful article. Often times, after us writers write our draft we don’t like to dive into the revision part of the process, which is key before publishing our work. Really enjoyed your post.

LikeLike

I don’t remember the last time I had my students write about their own writing. Need to do this again. Thanks for the reminder!

LikeLike

I’m actually revising a 420-page thriller for reprint purposes. It is a tremendous chore, seeing that I am already working from a final proof. But after having been away from it for over 10 years, I can certainly see more problems and new areas that need rewrites. I guess revision never stops. Although a writer must stop SOMEWHERE along the line and call it “finished.” Otherwise is will never get out there.

LikeLike