The first time I heard Megan Dowd Lambert’s name was during “The Power of Picture Books” Workshop I attended last fall at the Highlights Foundation. I returned excited about The Whole Book Approach (WBA), which is an interactive storytime model Lambert developed while working in the Education Department at The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art to help readers engage with the picture book as a visual art form. I tried it out with my daughter, as well as with groups of young children and was amazed at the ways we were able to work together to co-construct meaning from a picture book.

WBA was inspired from Visual Thinking Strategies, Dialogic Reading techniques, and Lambert’s own graduate study on the picture book at Simmons College. WBA is not a curriculum or a prescriptive methodology. Rather it’s an approach that values the physicality of the book and draws attention to how art and design can contribute to the reading experience. In WBA storytimes, teachers ask open-ended questions about picture book art and design while reading with children. Children’s responses are integral to the shared reading experience. Ideally, children synthesize the way the words, pictures, and design work together. When this happens, the result is an experience of reading with children as opposed to reading to them.

Charlesbridge released Reading Picture Books with Children: How to Shake Up Storytime and Get Kids Talking About What They See last month. If you teach elementary school, then it’s a must-have text! In an effort to share more about this wonderful approach with you, I interviewed Megan. As you’ll see, she’s a brilliant educator who cares about reaching every single child during storytime.

* * * * *

SAS: You spoke about the time it takes to develop children’s ability to read pictures in chapter seven. Would you explain why the development of children’s visual literacy skills is important for their success as readers (i.e., their engagement and comprehension). That is, would you talk about the time it takes?

MDL: First of all, written language is a visual representation of oral language, so in order to learn how to read, a child must understand that this squiggle “S” stands for this sound “SSSSS.” Therefore, supporting young children’s engagement with reading pictures as visual representations of the real world has unmistakable connections to learning how to decode letters and words as visual representations of sounds and language. These connections are grounded in the visual system that communicates between the eyes and the brain. The same kinds of communication that determine that “S” visually represents the sound “SSSS” help determine that J is a representation of a smiley face or of happiness, and that ♥ represents a heart or love.

It’s remarkable to me that a very young baby can look at a picture at understand it as a representation of a something in the real world. When my baby, Jesse, was just 7-months old we read Oliver Finds His Way by Phyllis Root, illustrated by Christopher Denise. In truth, it’s a book for older children, but we have a board book copy of it at home, and I was delighted by his response. The book includes a series of pictures of Oliver (a bear cub) roaring. Jesse began to echo my roars as I read aloud and then he roared on his own when I pointed to the pictures of the bear. How much of this was just echoing my sounds? How much of this was a response to a picture? I can’t be certain, but I know that this reading interaction felt different. It felt like he was really getting that the picture of the bear was more than an assemblage of colors and shapes and that it was a representation of a living, roaring creature. Some day he will understand that R-O-A-R is more than a squiggle, and then that it is more than a string of letters; he will understand that when put together in this order the letters visually represent the sound Oliver makes in the story, and the sound he (Jesse) makes when he sees a picture of a bear.

Apart from these sorts of connections, I also think it’s crucial to support visual literacy so that children can develop critical approaches to looking at art and understanding visual narrative and visual communication of information and ideologies. There are many reasons for this, including the fact that children receive so much visual stimulation and information online and in various media—including, but not limited to, their books. In my book I quote illustrator Chris Raschka (who also wrote the foreword) about this. He writes:

But we tend to take visual intelligence for granted. Or we dismiss it as simply the routine camera-like function of the eye. But eyes are much more than this. They think. They learn. We know there is value in the intelligence of the eye, we have big museums dedicated to it, but we’re not sure how to teach it. How do you teach color, form, line? You do it the same way you do words and sentences and ideas, by slowly increasing the level of complexity, depth and multi-layeredness. When the same care is taken in the use of formal elements of art—color and composition, for instance—as is demanded in art for adults, a child will inevitably become more visually intelligent, just as is the case in reading when care is taken in shaping the text of a story.[i]

I first encountered this piece when I was writing a paper about Chris’s jazz picture books[ii] while I was a graduate student at Simmons. It’s stayed with me ever since because I so appreciate how he rejects looking at art as a passive activity. Our eyes are not cameras, “They think. They learn.” I want the Whole Book Approach to support that thinking and that learning by making children’s responses to art and design as much a part of storytime as story is.

SAS: How can teachers incorporate the Whole Book Approach if they have limited time to read aloud during the school day?

MDL: First, I don’t advocate the WBA as a better, best, or only way to conduct storytime. This is one reason that the word “Approach” is so important! But teachers can easily try a few techniques to get kids talking about what they see and to overtly ground them in how visual thinking supports the work they do as writers or as students learning across the curriculum. After all, observation, making connections, and providing evidentiary thought are necessary skills in all kinds of learning.

In the back matter of my book I include a Resources section that includes practical tips for leading WBA storytimes, sample questions, a glossary, and suggestions for further reading. For now, here are a few concrete ways to start incorporating WBA into shared reading:

- Open a social studies lesson by using VTS-inspired questions to read a picture book image—perhaps the jacket, or maybe an interior spread:

- What do you see happening in this picture?

- What do you see that makes you say that?

- What else can we find?

Track how student responses provide insight into material culture, setting, character dynamics, and so on to reveal how close reading of art can provide ample information about a certain time and place. As the old saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words, so let a picture provoke students to build their historical knowledge by reading a picture.

- Compare a book with a portrait layout (vertically oriented) with another that has a landscape layout (horizontal). Ask students why the books are oriented differently. Do these layouts suggest that the stories will be focused on different things? For example, a horizontal layout may suggest a focus on a journey in the story as its form mimics the progression of the pages turning from left to right. A vertical layout may suggest a focus on a human character, or perhaps on a mountainous setting. Extend this into a writing lesson by asking students to justify a portrait or landscape format for the hypothetical picture book publication of their stories.

- Dig into an examination of endpapers. How do color choices evoke tone or highlight key characters or setting elements? Can students make a connection between the endpaper color and something in the jacket art? Why might this be significant? If there’s a design or motif, how does it relate to the story’s central theme?

- Invite children to consider the impact of typography. How does the visual appearance of a word impact how we make meaning from it? Anthony Browne’s Voices in the Park is a picture book I use in my chapter on typography because it uses four different fonts for the four different characters’ voices. But, take a look at any picture book and allow students to consider “typography as a semiotic resource.”[iii]

Through books, we outline a vision for our future.

SAS: How do you advise teachers who used to being the “sage on the stage” to think about revising their role so they can help kids make meaning from the paratexts, design, and illustrations of a book?

MDL: This question points to the constructivist, inquiry-based heart of the WBA. I think most teachers already try to balance the roles of “sage on the stage” and “guide on the side,” so I see the WBA as just another tool for them to add to their guide-on-the-side toolkit. The balance arises in teaching kids the book design and production terms by embedding them into a reading through open-ended questions, but then allowing students to respond with their ideas. For example:

“Take a look at how the gutter divides this picture,” (when looking at a picture that crosses the gutter to cover both verso (left) and recto (right) pages). “Why do you think the picture is divided up like this?”

Or:

“Watch how the artist makes uses the gutter (pointing to it) to divide his pictures. Tell me what you notice.”

In my book I point to the title page of Marla Frazee’s Hush Little Baby: A Folk Song with Pictures, which depicts a jealous little girl standing on the verso while her parents lovingly hover over her baby brother’s cradle on the recto. Here, the gutter isn’t merely accommodated; it’s used to reinforce the emotional distance between the girl and her parents.

In your WBA readings, students might note that the artist makes sure that no important details fall into the gutter. They might notice how the gutter can separate one character from another. They might notice how one character lunges across the gutter to attack another. Just let their observations and questions come to light as you center the book and its art and design as the focus of the discussion. Chances are, even if you don’t cover everything you’d noticed in a book, students will make insights you hadn’t noticed before.

SAS: Would you share suggestions for how to use the Whole Book Approach with special needs students and ELLs?

MDL: This is not my area of expertise, so I don’t want to be presumptuous in offering advice, but I can say anecdotally that when I visited inclusion classrooms and worked with ELL students during my decade of work leading visiting storytimes with The Carle, I simply made room for students to respond as I would in any classroom. Sometimes those responses would arise through nonverbal communication—children pointing to pictures or acting out a response—and I would observe them and bring them into discussion. I am always very eager to hear from teachers, librarians, and caregivers about using WBA with ELL and SPED students.

On a general note, I can say that when I led storytime at The Carle I heard from many parents (some of children with special needs) that they were “storytime dropouts” in other settings and that the interactivity and relaxed, child-centered environment I tried to create with WBA made them feel welcome at The Carle. Here, I think my experience as a mother of children with diverse learning and developmental profiles helped me to create a welcoming, inclusive atmosphere. I have six children, and one child has an ADHD diagnosis (inattentive type), another is dyslexic, and another has a communication disorder. Early in my development of WBA, I reflected on storytimes I’d attended with my son and realized the ways that reading at home differed from these group readings. He had to sit still, remain at a distance from the book, hold his comments and questions until the end, and quietly attend to the reading. Sometimes he was enraptured. Often, he was bored or felt excluded or shut-down. I realized that in either case he was placed in the position of passive audience member; that was not how things felt at home, where our shared readings felt like conversations and collaborative readings and where reading together was his favorite activity. I decided I wanted to try to bring some of the homey feeling of shared reading into the storytimes I led on behalf of The Carle. As noted above, the way I articulated this was that I wanted to read with children rather than read to them. I wanted storytime to feel like a conversation that I facilitated between children and books. In literacy education terms, I was shifting away from performance storytimes to develop my own model of co-constructive storytime practice that placed its focus on picture book art and design.

I can also offer a more precise anecdote, selected from many: Once I remember being in an inclusive public preschool classroom and I was reading Color Zoo by Lois Ehlert to the group. After we talked about the square shape of the book, a boy who was on the autistic spectrum started calling out the shapes he saw within the pictures—basically breaking down the representational collages into the shapes that comprised them. We rolled with it! We didn’t end up talking much about the animals in the pictures, but we centered this child’s contributions in the storytime and allowed him to take a leadership role in the conversation. This was all provoked by opening the storytime with attention to the layout of the book as an object.

SAS: You spoke about the way you can show reverence for quieter kids using the Whole Book Approach (i.e., praising their listening). But how do you help those quieter kids or kids who need more time to process their thoughts to speak up during a Whole Book Approach reading when there are more vocal peers surrounding them?

MDL: Again, paying attention to non-verbal responses can be helpful here. Facial expressions can betray thoughts a reticent child might otherwise keep to herself. Just last week I was leading a WBA storytime at The Carle and I showed the group the cover of Laura Vaccaro Seeger’s I Used to Be Afraid. I noticed a little girl catch her breath, and instead of calling on a talkative child who had his hand up, I asked her “What are you thinking about this picture?” She responded, “I’m thinking that book makes me a little nervous.” She was three-years-old, if that, so she wasn’t reading the title’s words; she was reading pictures. Her slight gasp let me know she was doing this, and I brought her into the conversation that way.

As we read through the book, a toddler who was in and out of attention at the storytime suddenly perked up when I turned to a page that included a picture of a wagon. He came over from the stack of board books he’d piled in front of his mother and excitedly pointed to the wagon. I looked at the books he’d gathered for his mom and realized that they all had pictures of cars and trucks on them—this was a kid who liked things that go! He hadn’t been engaged in storytime in ways that other kids were; he wasn’t sitting quietly, paying attention, and raising his hand to offer ideas and questions. But he was engaged in his own way, and when he offered this to the group I made it a part of our reading.

Other quick ways to bring quieter kids into discussion include methods I use in my teaching at the graduate and undergraduate level—I might simply say something like, “Would anyone who hasn’t had a chance to offer an idea like to say something about this picture?” This alerts the group that I realize some people have been quiet, and it opens the door for broader participation. Or, I might say something like, “I notice you nodding as so-and-so speaks. Why are you in agreement?”

SAS: How does validation and redirection help kids focus on a Whole Book Approach discussion?

MDL: This comes right out of my parenting experience, where it’s much easier to get a child to do something or to change a behavior if you first validate what he is doing and then redirect him to something else. I just saw my mother-in-law do this with the baby, actually: She has a shelf with three levels of framed family photos in her living room, and Jesse was very interested in them. As he pulled himself up to stand and started reaching for a frame, she went to him and picked up the frame, named the people in the picture and said, “But that’s not for baby, this is for baby,” and she handed him a toy and guided him to the rug. Simply saying no could have instigated a power-struggle or upset.

In a storytime context, I describe what I call “I have a dog” moments when if a picture book includes a picture of a dog suddenly kids are eager to tell you all about the dogs they know, those they’ve lost, and the dogs they wish they had. In moments like this I might say something like, “So many kids are talking about dogs!” (validation) And then I would find a child who’d been on the quieter side at storytime and ask something like, “You said you have a dog. Is it brown like this one?” and redirect the group back to the picture of the dog.

Think of the picture book as a meeting space. We all bring our own experiences to a shared reading, so it makes sense that a reading will provoke connections. Such responses are signs of engagement, and not mere interruptions. So, if you can find ways to capitalize on those moments, you will create a more inclusive dynamic. The best tool you have for redirection is the book itself as you guide students back to it as a common ground or meeting space for everyone in that shared moment.

SAS: How can teachers study with you?

MDL: I teach all kinds of classes at The Carle under Simmons’ auspices. In the spring 2016 semester I will teach a 2-credit graduate-level course on the Whole Book Approach from March 17-20. This course is open to non-degree students. For registration information and for information about other courses offered at The Carle and on our main campus in Boston, please contact me and I will connect you with our program director, Cathryn Mercier.

The Carle also regularly offers its own onsite Whole Book Approach trainings and outreach. Emily Prabhaker is the name of the educator who usually leads these workshops, and she is amazing.

And, I am also available for Skype visits, speaking engagements, signings, and other programs. I have started scheduling events into 2016 and would love to have more opportunities to spread the word about the Whole Book Approach.

SAS: What’s next for you?

MDL: In terms of my creative writing, I have a new picture book coming out in the spring, Real Sisters Pretend illustrated by Nicole Tadgell that is inspired by a conversation I heard two of my daughters having about adoption. I am in awe of what Nicole has done with her art to bring the sisters in the story to life in the pages of the book.

I’m also revising a sequel to my 2015 picture book A Crow of His Own, illustrated by David Hyde Costello. I don’t have a contract yet, but I’m working with editorial notes to revise a story I’m calling A Kid of Their Own, which features a goat and her kid moving to Sunrise Farm and a subplot about Farmer Kevin and Farmer Jay adopting a kid of their own.

I’m dreaming up possibilities for following up on Reading Picture Books with Children, too, but I don’t have solid plans yet. For now, I’m enjoying the positive reception it’s receiving and making plans to speak at various conferences and events in the coming year, including the ALA midwinter meeting in Boston in January 2016. I also continue to review books for Kirkus Reviews and the Horn Book Magazine, and I contribute to the Horn Book’s Books in the Home column.

Finally, I’m also committed to teaching at Simmons, where I have outstanding colleagues and amazing students. I’m thrilled about our recent partnership with Lee & Low Publishers to create the Lee & Low and Friends Scholarship aimed at increasing diversity in children’s book publishing, and I want to do all I can to support student and alumni successes in the field. It’s enormously gratifying and exciting to see Simmons alumni writing, editing, teaching, and advocating for children’s literature.

SAS: Is there anything I haven’t asked that you think I should have?

MDL: My parting note is that I hope my work with the WBA will be useful and inspiring to teachers, librarians, parents, and other caregivers who value children and their books. Children do not have a lot of power in our society, and on a micro-level I want storytime to be a place where they not only gain access to words and pictures, stories and ideas, but where their voices are valued and their insights and questions matter.

* * * * *

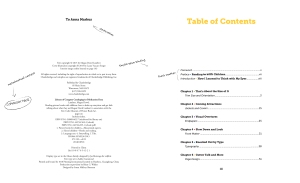

Take a look inside of Megan’s book. As you’ll see, there are notations written into the text to teach readers about aspects of the whole book.

Click on the image to enlarge so you can see the “handwritten” notations.

Click on the image to enlarge so you can see the “handwritten” notations.

Text © 2015 by Megan Dowd Lambert

Image © Simmons College

Used with permission by Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved.

* * * * *

Giveaway Information:

This giveaway is for a copy of Reading Picture Books with Children. Many thanks to Charlesbridge for donating a copy for one reader.For a chance to win this copy of Reading Picture Books with Children, please leave a comment about this post by Saturday, December 26th at 11:59 p.m. EDT. I’ll use a random number generator to pick the winners, whose names I will announce at the bottom of this post, by Monday, December 28th.Please be sure to leave a valid e-mail address when you post your comment, so I can contact you to obtain your mailing address if you win. From there, my contact at Charlesbridge will ship your book out to you. (NOTE: Your e-mail address will not be published online if you leave it in the e-mail field only.)If you are the winner of the book, I will email you with the subject line of TWO WRITING TEACHERS – LAMBERT INTERVIEW. Please respond to my e-mail with your mailing address within five days of receipt. Unfortunately, a new winner will be chosen if a response isn’t received within five days of the giveaway announcement.

Comments are now closed. Thank you to everyone who left a comment. Kristen’s commenter number was chosen so she’ll receive a copy of Megan’s new book. Here’s what she wrote:

I am currently involved in my first Mock Caldecott unit with my 5th graders. I wish I had read about WBA before I began the unit, as I think it would have helped me do so much more with an already incredible picture book study. Looking forward to reading the book!

This is really interesting! I would love to have a copy!

LikeLike

This was an interesting blog post! Thank you for interviewing the author! I can’t wait to get my hands on a copy of this book!

LikeLike

This is one of my favorite professional books for librarians and teachers in recent years – I’ve been recommending it to so many people I know! Of course, parents can also benefit from learning about the Whole Book Approach, especially since the experience of lap reading lends itself so well to discussing the pictures. Thanks for this great interview!

LikeLike

I am excited to learn more about this approach for reading with my own children (ages 3 and 1) and my Kindergarteners.

LikeLike

I would love to try this approach with my first grade students!

LikeLike

Post has me thinking how I can incorporate more opportunities for students to interact.

LikeLike

Thanks for the heads up on what will be a useful addition to children’s literature courses.

LikeLike

I love the Visual Strategies Approach. I had the great opportunity to learn it at the Eric Carle Museum when I lived in Western, MA. I would love to learn more through this book. Thanks so much for this post!

LikeLike

So interesting!

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing such wonderful information to teach children. We currently homeschool but I love working with kids in general and hope to put my skills to better use one day.

LikeLike

I am currently involved in my first Mock Caldecott unit with my 5th graders. I wish I had read about WBA before I began the unit, as I think it would have helped me do so much more with an already incredible picture book study. Looking forward to reading the book!

LikeLike

Great post! We use VTS in our reading and arts integration work at the Flynn Center and I certainly use this approach in reading with my own two young children. We move the visual imagery, word play, vocabulary, and ideas from the page and also push into kinesthetic, embodied interactions with the text, i.e. “Can you make a face like this character? What does that feel like? What might he/she be thinking in this picture? What tone of voice might they use?” It’s so fun, they are jumping out of their seats! I also find that asking kids to show, all together, is low-risk and inclusive. ELL and SPED, shy and introverted, gregarious and bold can all show and participate together.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was such a fabulous post. I’m excited to buy the book and learn more about the Whole Book Approach. I saw Katie Wood Ray at TC a few years ago talking about studying illustrations and I think that is the focus of her book In Pictures and In Words. I love the idea of an illustration study. Thanks so much for sharing this!

LikeLike

I work with English learners, and find picture books to be helpful. Your post has expanded my thinking and I will look more closely at student expressions when looking at the pictures. I love the part about catching the expressions on the quiet children’s faces!

LikeLike

I really enjoyed reading this article. I know a little about the Whole Book Approach from my visits to the Carle, but this article made me want to sign up for your class!

LikeLike

Wow, reallly wonderful post that could have such a positive impact on kids,

LikeLike

Thank you for introducing me to this idea! I have often talked to students about “author’s/illustrator’s choices” with illustrations, pictures, text organization, but this takes it to a new level. I think it helps children generate ideas for their own writing as well. Reading as Writers and Writing as Readers!

LikeLike

Ahhh…the power of picture books. When I read to my children when they were young, we were always completely immersed in the entire page/book. We’d discuss the background (in the Babar books) and the way the elephants were dressed; we’d delight in the cavortings of Curious George pictured so delightfully; and we’d “read” the expressions on characters’ (animals) faces as in the Maple Grove Farm series. I might add that when ENL learners “read” a book, the visuals are where they are getting most of their cues. Thanks for the informative post.

LikeLike

Great ideas to share my favorite, Picture Books! Thanks.

LikeLike

I love the idea of the annotated picture books to open the discussion about the aspects of the book. Great for any age/grade!

LikeLike

This is a fascinating concept! We use our read aloud questions to develop comprehension skills in kindergarten, but I’ve never explicitly, solely focused on the illustrations. It makes so much sense!

LikeLike

Fantastic post! As an adult I have a tendency to focus on the words, rather than the pictures. In recent years I’ve come back toward having students examine both and how they work together. This approach seems like a fantastic way of involving children more actively in the reading process.

LikeLike

Thank you! I am always looking for new ideas to help round my thinking, when it comes to teaching: new ways to engage student’s thinking. I especially like suggestions for new picture books to share with students.

LikeLike